I have a large collection of books in my home. When other teenagers were busy collecting Smash Hits and novels of the sort they probably shouldn’t have been reading, what I loved on my shelves were really old books. There were grubby, dusty cloth-covered ones, and some with covers of kaleidoscopic swirls of marbled paper and spines (I later learned the technical term for a spine in the old book world is, slightly confusingly, the “back”) of silky, shiny leather. As my collection grew over the years, I purchased some Victorian volumes with gilded patterns on their covers. I must admit I wasn’t particularly interested in the words inside the books when I was younger; I was attracted to their decorative qualities and their age. I liked them merely because they were old things. so that when I handled them I was sort of holding the past.

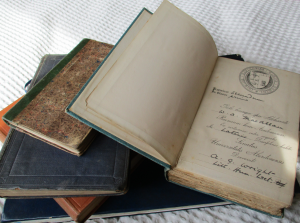

I gradually became a little more interested in the contents of my dusty old volumes, especially of those that related to poetry and social history. And recently another thing about them has begun to interest me. So many older books have bookplates inside them, or names written at the beginning. It has occurred to me that the ownership of books is an interesting subject. It has also occurred to me, being quite keen on amateur genealogy, that with so much information on ordinary people of the past now available on the internet, that I might be able to trace the previous owners of some of my books. Where books have had more than one owner, do they begin with a wealthier person and end up in a less well-off home, as clothing used to? What kinds of families had what kinds of books? How far did books travel from their place of publication?

Over the next however many weeks/months/years, I will look at my books and try to find out something about their original owners, where they are known. Of course, this isn’t necessarily a poetry-related study, although some of the books will be poetry books, and I may be inspired to write poems about some of them. I have begun by writing a verse inspired by names in books. I invented my own name and date, although I daresay a person of that name has existed!

READER

That book on my shelf has a sunlight-sapped spine,

And it gasps to reveal its original lover,

Alice Mackenzie, 1929.

This book that I grasp shall not ever be mine

In the way it belonged to that faceless another

Who opened the book and inscribed that proud line.

The book that I shelter is never so fine

As it was when the wrapping was prised from its cover

By Alice Mackenzie, 1929.

A book with a title in full gilded shine,

A book with a world in its words to discover

When she opened the book and inscribed that proud line.

They say, now, that books could be facing decline

As our crystals and pixels may threaten to smother

Alice Mackenzie, 1929.

A new thing, an old thing, a relic, a sign

Of past times, of kept thoughts and the life undercover

Of Alice Mackenzie, 1929,

Who opened the book and inscribed that proud line.

EXPLORATIONS IN THE OWNERSHIP OF SOME OLD BOOKS

Some really interesting owners and life stories have emerged from my random collection of dusty old volumes!

TALES OF THE COASTGUARD, published in 1884.

Title: Tales of the Coastguard and Other Stories.

Publisher: W. and R. Chambers, London and Edinburgh, 1884.

Bookseller: Bookseller’s stamp on front flyleaf: S. Dawson, Bookseller Stationer, Hyde.

Comments on the book itself:

This volume has a green cloth binding with stamped decoration, some gilded. There are several engravings inside. It is unclear whether the stories are complete fiction or based on factual memories. This quote from Chapter IV, The Smugglers’ Hostage, gives an idea of the nature of the writing:

Only one of the seamen wounded in the brush with the smugglers previously narrated recovered. The other, James Norton, having been hit grievously on the left knee-cap, it was found necessary to take off the leg, and the poor fellow sank under the operation.

Owner’s name: Harry Jackson.

Owner’s inscribed date: No date.

Place: None given.

Bookplate, or name only? Name only.

Owner details revealed by research:

Not having much information to work with, the identity of the original owner of this book is speculation. However, taking the town of the bookseller as a starting point, I did find a family living in Hyde, Cheshire, with a son called Harry, born in 1881 in Ashton-Under-Lyne. The 1881 Census (via FindMyPast website) lists Sarah and James Jackson with 7 children, one of whom was Harry, living at Well Meadow. Mr Jackson was a Master Blacksmith, employing 2 men and 2 boys. Two older sisters worked as cotton weavers and Harry’s brothers were an apprentice boiler maker and apprentice blacksmith. This Harry Jackson would have been too young to have read or written in this particular book in 1884, when it was published, but he could have come by it a few years later, or written his name in it later on. Perhaps the volume took some years to get to the bookseller in Hyde, and/or perhaps it was not new when the Jackson family took possession of it. Harry grew up to become an assistant in a grocer’s shop (1901 Census) at which point his father had become a “Drilling Machine Smith, Boiler Works”. After this he could not be found in the records, except that there is a record of a death of a Harry Jackson in Hyde in 1941.

THE GOLDEN TREASURY, published in 1916.

Author: Francis Turner Palgrave (selected and arranged, with notes by)

Title: The Golden Treasury.

Publisher: Humphrey Milford, Oxford University Press, 1916.

Bookseller: No information.

Comments on the book itself:

This volume is Palgrave’s Golden Treasury (first published in 1861) with “additional poems” from up to the end of the nineteenth century. It is bound in dark blue cloth, with a central gilded stamp on the front cover. It is an anthology of poetry, including some of the most famous English writers, such as Shakespeare, Milton, Keats, Wordsworth and Shelley. The Treasury is still in print today and is one of the best-selling poetry anthologies ever to be published.

Owner’s name: Annette Wakeling.

Owner’s inscribed date: 1920.

Place: Hotham Road School.

Bookplate, or name only? Bookplate; school prize for “General Work, especially English” (signed by A. Thompson, Head Teacher).

Owner details revealed by research:

I am relatively confident that the identity of the first owner of this book was Annette Wakeling, born in 1909 (from 1911 Census, via The Genealogist website) who lived in Putney, where the school above named was sited. Her family lived at 50 Sefton Street, Lower Richmond Road. Her father was a bootmaker, who worked from home, named William. Her mother’s name was Edith. Annette had 3 brothers (whose places of birth suggest that the family had previously lived in Fulham) and a sister, Edith. Annette was the youngest child in 1911. There were few signs as to what happened to Annette later in life. I did find a record of a death of an Annette Emily F. Wakeling in 1980, born, according to that record in 1908, who died in the Redbridge district, Greater London. This may not be the same person, but perhaps she lived a single life without children. An Annette appears on the 1939 Register, living with an Eileen Wakeling in Wandsworth, again with a 1908 date of birth. The handwriting indicating her occupation is hard to read and I think has been mis-transcribed as “Carpenter Capacitor”; the second word could be “operator”, but whether Annette used her early talent in English later in life remains a mystery.

AN ESSAY ON MAN, published in 1792.

Author: Alexander Pope.

Title: An Essay on Man, in Four Epistles, to Henry St. John, Ld. Bolingbroke.

Publisher: Printed by R. Morison, Junior, for R. Morison and Son, Booksellers, Perth; and N.R. Cheyne, Edinburgh, 1792.

Comments on the book itself:

This is a small volume bound in what I think is known as tree calf (i.e. very fine, soft calf-skin or leather with a natural tree-shaped pattern) with a gilt tooled design around the edges of the boards (covers) and five little golden urns down the spine. The work itself, by the great English writer, Alexander Pope (1688-1744), is a long rhyming poem which Pope said came from an idea “to write some pieces on human life and manners”. He claims to have decided to write this in verse form to make his arguments more memorable to the reader and because he found it easier to be concise “without becoming dry and tedious” writing in this form instead of prose.

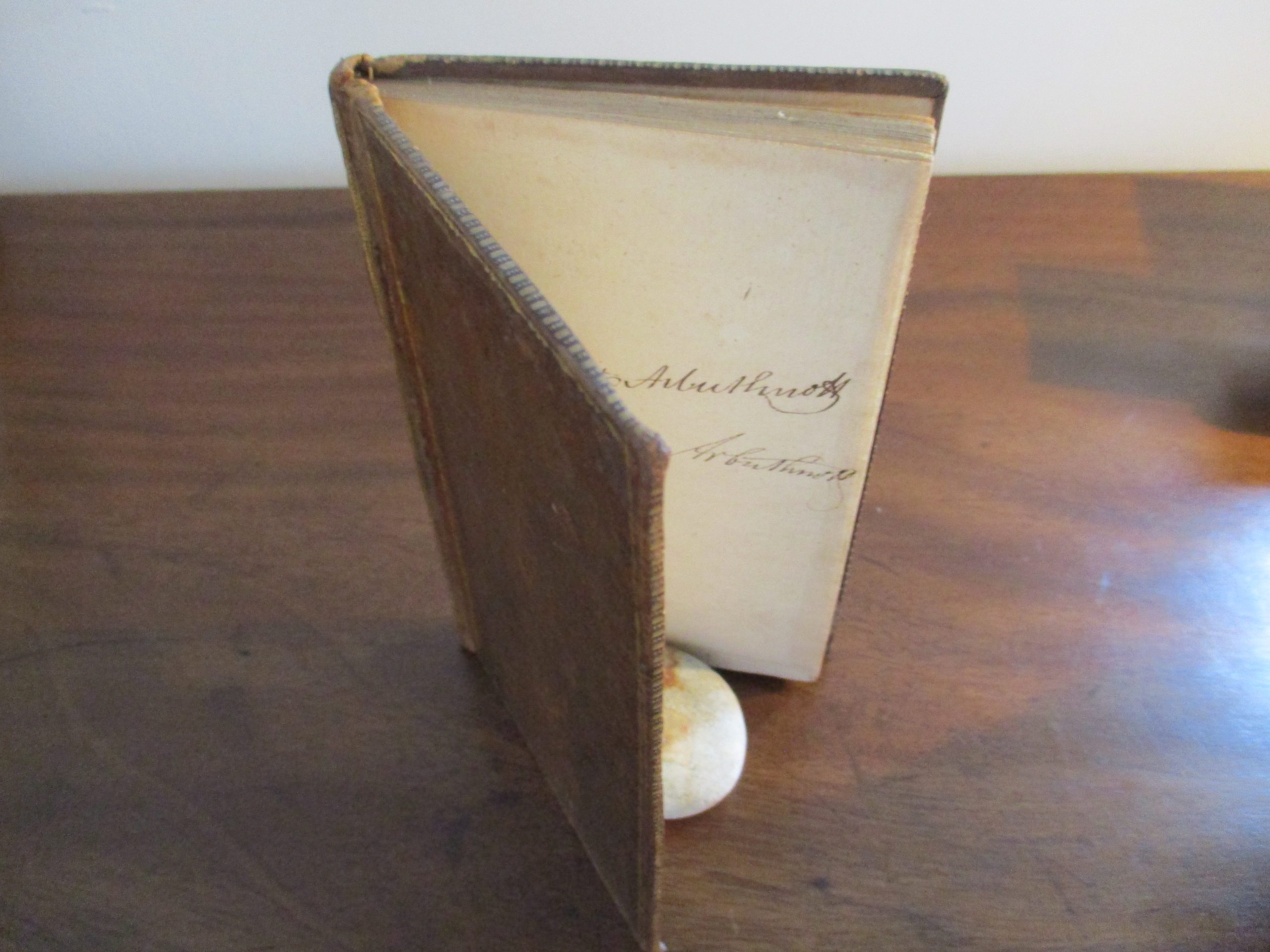

Owner’s name: Viscount Arbuthnott/Lord Arbuthnott

Owner’s inscribed date: No date.

Place: Arbuthnott House, near [unreadable word]

Bookplate, or name only? There is no bookplate. “Viscount Arbuthnott” is written twice in ink on the first leaf of the book. “Lord Arbuthnott” appears on the last leaf of the book, in pencil, together with “Arbuthnott House”.

Owner details revealed by research:

As the book was printed in 1792 it could have belonged to either the 7th or 8th Viscounts, whose family had inhabited Arbuthnott House in Kincardineshire, Scotland, since the thirteenth century. The 7th Viscount lived from 1754-1800; his son from 1778-1860. They were both named John. The current Viscount is still in residence at the family seat, which has been recently renovated and is sometimes open to the public. Wikipedia claims that the 8th Viscount was the first to spell the family name with two t’s, so perhaps this indicates that he was indeed the original owner of this volume, as the name is written in this form. This John Arbuthnott was a soldier and member of the House of Lords, representing Scotland, and a portrait of him by David Wilkie may be viewed on www.artuk.org. This shows him as a dashing character with regency-style unwigged fair hair, wearing what looks like a military-style coat beneath a fur-trimmed cloak; clothes presumably signifying his roles as member of the House of Lords and as a soldier. He sat in the Lords from 1818 and the portrait has been dated to around 1840. A large dog stands beside his seated figure, his hand resting on a piece of paper.

There is a connection between the Arbuthnott family/clan and Alexander Pope. Pope knew a man called Dr Arbuthnot, a renowned Scottish doctor, writer and scholar who was born in Kincardineshire (where Arbuthnott House was situated) who lived from 1667-1735. Pope wrote a poem dedicated to Dr John Arbuthnot in 1735 (Epistle to Dr Arbuthnot). According to the Norton Anthology of English Literature (1979 edn.), “Arbuthnot, from his deathbed, wrote to urge Pope to continue his abhorrence of vice and to express it in his writings”. Dr Arbuthnot apparently claimed that he was related to the Viscounts.

(Information is from Burke’s peerage, Wikipedia and other websites on Arbuthnott history, including the family’s current website www.arbuthnott.co.uk, which includes pictures of Arbuthnott House, where this book once belonged.)

THE MILL ON THE FLOSS, published in 1901.

Author: George Elliot.

Title: The Mill on the Floss (George Elliot’s Works, The Warwick Edition, Vol. II).

Publisher: William Blackwood and Sons, Edinburgh and London, 1901.

Comments on the book itself:

The book is bound in black calf-skin with a little gold decoration on the spine, which is not in good condition. A well-known work of Victorian fiction by this pioneering female writer.

Owner’s name: Annie M. Broome.

Owner’s inscribed date: 1901 (thought at first it was 1907, but I think 1901 is more likely).

Place: Wilmslow, Cheshire.

Bookplate, or name only? There is no bookplate, but the book was given as a school prize. The teacher has hand-written the dedication which reads:

II Prize for Mathematics

Highfield School

Wilmslow

Dec 13th 1901

Following these words, the teacher has signed her name: S.B. Hull, B.A.

Owner details revealed by research:

Before coming to the story of the holder of the Mathematics prize, I feel I should briefly mention S.B. Hull, as she was presumably the book’s purchaser. I was unable to verify Mrs Hull’s name before marriage (for married she was) so there is little I can know about her earlier life, except that the “B.A”. she has apparently written after her own name is intriguing. Standing for Bachelor of Arts, it would make her something of a pioneer in women’s education in Britain, as it indicates that she had gained a university degree. Although women had increasing access to some form of education throughout the nineteenth century, more than half remained illiterate by the 1850s. In 1878, however, it became possible for the first time for women to gain a university degree at the University of London. Other institutions followed, with Oxford University finally admitting women to degrees in 1920 – although Cambridge did not follow suit until 1948. As Sarah Hull was born about 1859, she would have been 20 years old in 1879, so could potentially have been one of the first university educated females in the country. In 1901, according to Census records, Sarah Hull, who had been born in Bradford, Yorkshire, lived with her husband William D. Hull in Swan Street Wilmslow. It looks as if she was the better educated of the couple, as William is apparently both a “Commercial clerk” and a “concreter and asphalter”. Her occupation is described as “Head Teacher in Private School”.

In finding Sarah Hull on the Census, I also found the young girl to whom the book was given, Annie M. Broome, because it turns out that she lived with the Hulls at the school as a boarder. There are no other boarders listed (other members of the household include an assistant teacher, Florence Watts, a cook and a housemaid), but presumably Annie was not the only pupil. If she was, she doubtless won a lot of prizes!

I looked back at the 1891 Census for more information about Annie’s family and what was potentially a rather sad story emerged. She was born in Oldham in 1887, daughter of William Bird Broome, an estate agent, and his wife, Sarah. There was a younger sister, Marjorie, plus 2 servants at 137 Windsor Road, Oldham. However, it appears that Annie’s mother died in 1894, when Annie was only about 7 years old, and her mother still in her twenties. Intriguingly, a baby of the same name died towards the end of 1893 (Sarah Broome’s death was registered in the first quarter of 1894), so it seems quite possible that a stillborn child was named after her mother, who died herself soon after, perhaps from the effects of childbirth. Obtaining the relevant death certificates would be the only way of knowing for certain.

In 1898, Annie’s father married again – a lady called Agnes. They had no children of their own. Annie’s sister, Marjorie, seems to have remained with her father, but Annie must have soon been sent away to school. The 1901 Census shows that the Broome’s (Mr Broome was now an estate agent and accountant) had moved to a fine new 3-storey home called Failsworth Lodge off Oldham Road. This property had sat in a large wooded estate, but in the late nineteenth century, a railway line had been put through. The house had apparently belonged to Joseph Grimshaw, a hatter, at the end of the century. Perhaps Mr Broome bought it from him at a bargain price because of the encroachment of the railway. However, Annie Broome did not get to enjoy the grand new house as much as her sister did, but was sent to live with a schoolmistress and her husband. Was there friction between Annie and her new stepmother, or was she just very intelligent and deemed to need a good school? For whatever reason, this meant that at times, at least, Annie was the only child in the house and school. At least she was good at Maths! I wonder whether she was ever able to take a university degree like her teacher?

CRIMINAL TRIALS, published in 1832.

Title: Criminal Trials, Vols. I and II. The Library of Entertaining Knowledge.

Publisher: London: Charles Knight, Pall Mall East (and 4 other listed publishers) MDCCCXXXII (1832). Printed London: William Clowes Stamford Street.

Comments on the book itself:

Bound in black leather with marbled edges. The back (spine) of the second volume is in poor condition with two missing pieces of leather, exposing the cardboard beneath. The contents cover famous historical trials, with an introduction by David Jardine, Middle Temple, 1832.

Owner’s name: John Medley Doble; S.R. Schofield.

Owner’s inscribed date: 1881; 1941.

Place: Second owner’s name accompanies the place name Lelant (which is in Cornwall).

Bookplate, or name only? Two bookplates and inscriptions.

Owner details revealed by research:

The earliest indication of an owner for this book is 1881, although, approximately fifty years after its publication, that seems unlikely to have been the first. John Medley Doble’s bookplate is here, decorative and printed in black and white with the name of the bookplate’s designer, “Harry Soane, sc. London” and a Latin motto. I discovered that a John Medley Doble had been born in Peckham in around 1845 and may have moved to Cornwall in the 1870s and may have died in the 1920s. His parents (Richard Doble and Anne Michel) were Cornish but living in London. The 1881 Census shows someone of probably the same name, and with the matching place and date of birth, in Penzance (John M. Doble) who is a bank cashier. John was married to Fanny and had sons called Gilbert and Francis who lived at 13 Morabb Road where they also kept two servants. Viewing Morabb Road on Google Earth, you see a delightful street of bay-windowed, stone-faced Victorian houses, semi-detached and terraced with attic windows. The road looks down to a sea view. It appears light and airy and as if it would be a place where a middle class family might enjoy good quality of life. Our book was at some point to move from its hopefully happy home, and it seems likely that it came into the hands of the next recorded owner in Cornwall, as he had connections there as well.

Seymour Redmayne Schofield has a printed bookplate in one of the volumes of Criminal Trials and has also written his name in the other. One incidence of his name is associated with the date 1941 and “Lelant”, which is a place in Cornwall. He turned out to be from a successful and rather famous family. Benjamin Seymour Redmayne Schofield, as his full name seems to have been, was born in 1899 in Ormskirk, Lancashire and died in Ipswich, Suffolk in 1973. He appears on the 1901 Census living in the household of his Uncle with both his parents, who were Walter E. Schofield and Murielle Redmayne. He also turned up on various passenger lists, whilst he was a child, travelling to and from the United States. As I delved deeper into his identity it became obvious why. His father was in fact an American immigrant to Britain, who had been born in Philadelphia. And when I looked carefully at the Census records, I could see that he was some kind of artist. He turned out to be the renowned painter, Walter Elmer Schofield, who painted mainly landscapes in both Europe and the United States and whose paintings hang today in many public galleries throughout the world.

In the 1920s, the family lived in Suffolk, England, at High House in Otley where Walter Elmer Schofield painted the local landscape, including his work, The Red Barn. In the later 1930s however, they were on the move again to Cornwall, where Schofield joined the community of artists in St Ives and bought Godolphin House, Kerrier. This substantial and grand house remained in the family until very recently. In 2018, it was taken over by the National Trust and will continue to be preserved and opened to the public.

Seymour Redmayne Schofield seems not to have become an artist, but his younger brother, Sydney Elmer Schofield did attend the Slade School of Art, following an education at Bedford Grammar and Christ’s College Cambridge.

S.R. Schofield married Enid D. Ratcliffe in Kerrier in 1938. I have not been able to find out what his profession in life was. Looking at the provenance of some of his father’s paintings that have sold at auction, Seymour clearly owned some of them, so Criminal Trials would have been in fine company in his home.

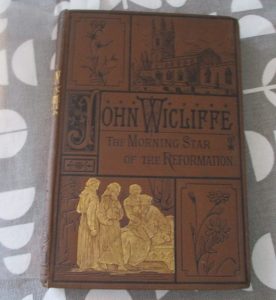

JOHN WICLIFFE by David J. Deane.

Title: John Wicliffe: The Morning Star of the Reformation.

Publisher: S. W. Partridge & Co., 9 Paternoster Row, London.

Comments on the book itself:

This volume has a brown cloth decorative binding with some gilding. It has a number of engravings inside. The biography within is a detailed account of Wycliffe’s life (96 pages) and is heavily pro-Protestant. A flavour of it can be obtained from this brief quote:

The resistance of Edward III, and his parliament to the papacy without had not suppressed the papacy within. Monasteries abounded. In too many instances they were the abodes of corruption…

Lands, houses, hunting grounds, and forests; with the tithings of tolls, orchards, fisheries, kine [cows], wool, and cloth, formed the dowry of the monastery. Curious furniture adorned its apartments; dainty apparel clothed its inmates; the choice treasures of the field, the tree, and the river, covered their tables; while soft-paced mules carried them by day, and luxurious couches bore them at night.”

At the end of the book, bound in with it, is a publisher’s catalogue of other titles. The ones advertised here all have moral or religious themes: Biblical companions, hymns and improving or inspiring stories. Titles such as, My Darling’s Picture Book; Come Home, Mother; Scrub, the Workhouse Boy and Uncle John’s Anecdotes of Animals and Birds suggest that some were specifically aimed at children. They come in different price brackets, from Seven Shillings and Sixpence down to Fourpence. This title comes in the list of One Shilling books, but apparently the cloth binding cost extra.

Owner’s name: H.J. Langcaster

Owner’s inscribed date: November 7th 1886

Place: Swindon, Wiltshire.

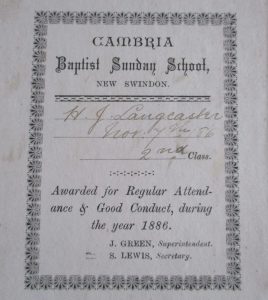

Bookplate, or name only? A school prize bookplate, reading as follows:

CAMBRIA

Baptist Sunday School,

NEW SWINDON.

H.J. Langcaster

Nov 7th 86

2nd Class

Awarded for Regular Attendance & Good Conduct, during the Year 1886.

J. GREEN, Superintendent.

S. LEWIS, Secretary.

Owner details revealed by research:

The boy who was presented with this book was, I believe, one who appears on the 1881 Census as John Harry Langcaster (the identification is fairly convincing as the surname has managed to maintain its distinctive spelling when passing through the hands and minds of the Victorian census enumerators and modern transcribers), although the order of the initials suggests that he was known as Harry John by the time he received his prize, when he was aged about ten. Five or so years before his good attendance at Sunday School, he was living at 19 Clifton Street, New Swindon: New Swindon was then a modern part of town that had been built after the coming of the railway, presumably largely to house workers for that industry. Old Swindon merged with the new part of town around 1900.

Harry’s home looks to have been a pleasant one. A photograph of the street in around 1910 (there are a number available on the internet) shows a reasonably wide road lined with terraced houses having downstairs bay windows. Modern house details reveal them to be generally 3-bedroomed. The street looks very clean, neat and rather smart. Harry’s father, William (originally from Lincolnshire) worked for the Great Western Railway as a coach builder. His mother, Hannah, born in Yorkshire, appears not to have worked, suggesting that William’s wage was enough to sustain the family well enough. The family seems to have moved around a number of times, from one industrialised part of the country to another, as Harry had been born in Nottinghamshire, whilst his younger brothers, Robert Ernest and Josh Edward were born in Lincolnshire and Derbyshire respectively.

Harry grew up to be a railway coach builder himself. In 1901 he lived in Nottingham with a young wife from Swindon called Ada. Interestingly by 1901 he has become John Harry on the records once more. Harry/John Harry and Ada had at least two sons, Harry James and Frederick Ernest. Frederick was, for some reason, born in Ealing, London.

The Great Western Railway works where Harry’s father must have worked are now the brilliant STEAM museum.

I slightly wonder what Harry thought of his Sunday School Prize and whether he actually ever read it. It is hard to imagine a ten-year-old today enjoying such a book!

A note on the Baptist Chapel

Cambria Baptist Chapel is now a private home. Pictures of it are available on www. oodwooc.co.uk/ph_sw_cambria.htm. It was built in 1866, particularly for the use of Welsh ironworkers moving to Swindon to work for GWR. Many Baptist Sunday schools focused their efforts on the poorest in society. The Wycliffe Baptist Sunday School in Birmingham (established in 1860) started an evening meeting for a class of children “too rough and rude and ragged to be in the morning and afternoon schools” (See The Baptist Quarterly, Victorian Sunday Schools in Birmingham from the website biblicalstudies.org.uk). By the time Harry was at the Sunday School, improvements in national education and schooling provision for all meant that the focus of teaching would have been more on religious education than reading and writing. The book that Harry was given suggests that the Sunday school teachers expected him to have a high level of literacy – or perhaps expected his parents to be able and willing to read it to him.

THE PARENT’S ASSISTANT, by Maria Edgeworth.

Author: Maria Edgeworth.

Title: The Parent’s Assistant, or Stories for Children.

Publisher: George Routledge and Sons Limited, London.

Bookseller: No information.

Comments on the book itself:

This volume is “A New Edition, with thirty illustrations and five coloured plates by F.A. Fraser” of a book first published in 1796. There is no publication date in my copy, but the illustrator was born around 1846 and seems to have illustrated a number of books in the 1870s and 1880s. The book is bound in dark blue cloth, stamped with stylised flower forms that look very “art nouveau” in style, so I guess the volume could have been produced any time between the 1890s and 1910s. When first published in the eighteenth century, Maria Edgeworth’s book (a collection of short stories and some plays) became a hugely successful volume; and as my copy shows, it remained popular more than a century after it was written. The tales all have moral and behavioural lessons to teach the reader and in the Preface, Addressed to Parents, the author outlines her philosophy of child-rearing and education, in which she quotes Dr Johnson. Her purpose and inspiration for the book is to “provide antidotes against ill-humour” and the inclusion of descriptions of bad behaviour are because, “in real life they must see vice, and it is best that they should be early shocked with the representation of what they are to avoid. There is a great deal of difference between innocence and ignorance”. And of course, naughtiness has always made a great story! This book is now considered to be an important step in the development of literature for children and is especially noted for its inclusion of a central, relatable character (Rosamund) who is first introduced in these stories.

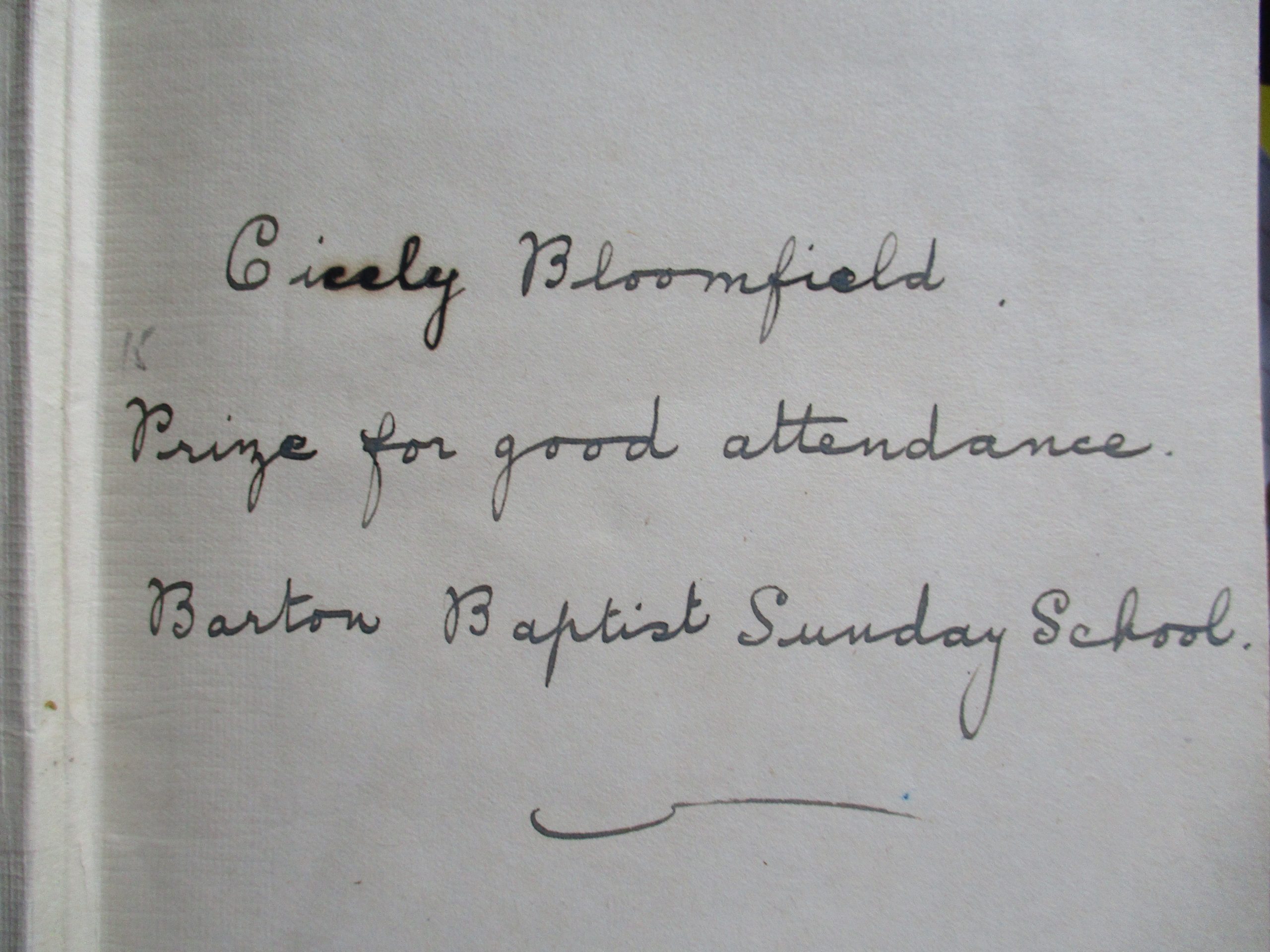

Owner’s name: Cicely Bloomfield.

Owner’s inscribed date: No date.

Place: Barton.

Bookplate, or name only? No plate, but is inscribed, in ink, as follows:

Cicely Bloomfield.

Prize for good attendance.

Barton Baptist Sunday School.

Owner details revealed by research:

A likely owner for this book is Cicely Bloomfield of Great Barton, Suffolk. According to the 1911 Census she lived in Mill Road, Great Barton, a settlement just a few miles outside Bury St Edmunds. I bought the book from a dealer in Felixstowe, so it seems to have winged its way around East Anglia.

In 1911, Cicely was only 4 years old, so I assume she was given her prize maybe 4-6 years later, possibly during the First World War. I wonder then whether the book was new or secondhand when she received it. Cicely lived with her parents, Arthur and Sarah Bloomfield, in the residence of her grandfather (her mother’s father), Frederick Cheltenham, who had been widowed. Mr Cheltenham was a “Horsekeeper on farm”. It happens that Great Barton has a tradition of links with the horse-racing industry, so there would be no shortage of horses to take care of in the area, whether of the working or racing variety. Cicely’s father worked as a farm labourer. There were 3 other children in the home in 1911, all very young and close in age: an older boy, Victor, aged 5 and 2 younger ones, Walter, aged 2 and Gladys, an 8-month old baby.

The Sunday school where Cicely was to receive her prize was probably on the site of what is now Great Barton Freedom Church, a 1950s building on the site of a corrugated iron building in Mill Road dating from the 1890s, near where the family lived.

Looking into the history of the area, I uncovered an intriguing story concerning a significant local event that Cicely would certainly have known about and may have witnessed. In 1914, the local manor house, a grand Elizabethan mansion filled with fine furniture, paintings and books, suffered a serious fire; ashes from which it never rose again.

The fire at Barton Hall was reported in newspapers all over the country, with pictures of before and after the disaster appearing in the London Illustrated News. A full report, with photographs, was printed in the Bury Free Press, which can be read (although not always easily due to reproduction quality issues) in online images from the British Newspaper Archive.

Owned by Sir Charles Henry Bunbury, the “magnificent mansion” that the newspaper described had been occupied at the time by Sir John and Lady Smiley. Many well-known people had visited there over the years, including in fairly recent times, King Edward VII when he was Prince of Wales. A number of guests had been staying for what was presumably a typical country house weekend on January 16th, 1914. There had been a dance after dinner that evening, ending at midnight. It was only about 30 minutes later that a fire broke out towards the top and middle of the building, and although the fire brigade and estate workers came to help, assisted by persistent rain, most of the building would be lost. Much of the furniture was saved, and many books and paintings, but items had to be piled up outside, uncovered in pouring winter rain. Valuable clothes and jewellery perished. One guest apparently reported that he could save “nothing except his gun and golf clubs”.

The newspaper reporter (recorded only as “Our Own Representative”) gave a superbly vivid description of the tragedy. “The glare of the fire could be seen for miles around”, reports the Bury Free Press. “Employees hurried to the scene…in the pouring rain, which continued all night long, and an awful, yet grand spectacle met the gaze”. Eventually the floors “fell in with a loud crash, and huge volume of flames and sparks shot up high into the air. Bedsteads, chairs, tables and other articles of furniture came down with the floors.” The vivid description continues: “The entrance hall for halfway was intact and emptied, but beyond the glass door it was impenetrable, for it was all one mass of heat, and the grand staircase was enwreathed with the lurid flame.” As the spectators watched, “Now and again a terrified rat would run…and take shelter in a heap of furniture.” Collapsing stone, plumes of flame and sparks and piles of bricks rained down until eventually 2 water tanks that had been secured at the top of the building “fell at about 4.30”.

Of course, Cicely’s family would have seen the charred ruins of the Hall, but there is some doubt as to whether she would have experienced the conflagration itself. The newspaper reports that not everyone who lived in the vicinity necessarily knew about the fire as it happened; “Many persons residing in Barton Street, a short distance away, knew nothing of the catastrophe until 8 o’clock Saturday morning”. Had Cicely or any members of her family watched the fire, it was surely a spectacle they would always remember and was no doubt a topic of neighbourhood conversation for some time.

Items that were rescued from the house were taken to various local buildings for storage, so a number of community activities were temporarily halted. The Sunday school, presumably the one Cicely so diligently attended, was cancelled that week.