Looking back at the history of writing for children, not all well-respected authors considered that poems were suitable reading. Anna Laetitia Barbauld (nee Aikin, 1743-1825) was a significant figure in late Georgian and early nineteenth century educational theory and a respected writer. Described by the Poetry Foundation as “a figure of eminence in the world of letters”, Mrs. Barbauld, as she became known, was brought up in the surroundings of a school run by her father and also went on to marry a clergyman (Rochemont Barbauld) who also ran a school. She was interested in current affairs and wrote passionately about contemporary issues in her poetry, through which (using conventional classical verse forms) she sought to influence hearts and minds, promoting the moral codes rooted in her non-conformist Christian religious conviction.

Given that she was an educator and a poet, you might expect her to be a keen advocate of children’s verse. But no. Mrs. Barbauld seems to have taken poetry so very seriously, and held it in such high regard as a literary form, that she considered that the inevitable “dumbing down” that would have to occur to make it comprehensible to the young would be sacrilege. Here is what she said on the subject in the Preface to her book Hymns in Prose for Children, first published in 1781:

But it may well be doubted whether poetry ought to be lowered to the capacities of children, or whether they should not rather be kept from reading verse till they are able to relish good verse; for the very essence of poetry is an elevation in thought and style above the common standard.

However, she does recognise the value of rhythm and sound in writing for children, especially to help them to commit passages to memory, and since she intended passages from her book to be learnt and recited, wanted to use a writing style that would aid this. She describes this way of writing as measured prose which she suggests is, nearly as agreeable to the ear as a more regular rythmus. It seems apparent, and not just in the religious content of Hymns in Prose, that she has taken inspiration from English translations of the Bible and most particularly, I would suggest, the Book of Psalms. If you read the King James Version, which had been modernised in 1769 and was presumably the Bible Mrs Barbauld would have known, you find in the Psalms that sentences are broken up into several phrases or clauses by punctuation, with each phrase having a similar number of stressed syllables, giving the effect of a repetitious rhythm. Mrs Barbauld often does the same thing, although her sentences can be a lot longer than Biblical ones, with sometimes 50 or 60 words divided by numerous commas, semi-colons or colons. She typically has between 3 and 6 stressed syllables in a sentence, or clause within a sentence, although sometimes she has as few as 2 or as many as 8. She seems to be slightly more regular in her use of stressed syllables than the Biblical Psalms (my research here was based on a very quick and random skim read of the texts!) but with a less regular pattern than that other well-known and frequently recited religious text, The Lord’s Prayer, which is a 4 stress line, followed by 3, then 4 again etc. The phrases in The Hymns are invariably, although not always, written in “trochaic” meter, or almost so: that is a “dum-de-dum-de-dum” rhythm, with words chosen so that syllables are paired with a stressed syllable followed by an unstressed one, creating a sort of verbal drum beat. Examples of this from Mrs Barbauld’s text are as follows:

God is the Sovereign of the King;

Trees that blossom and little lambs that skip about.

I will show you what is strong.

So there are clearly poetic elements in Mrs Barbauld’s prose, and, in fact, there are times when she seems to struggle to keep the poetry out! Especially in the sections of the book where the subject is nature. Take this passage, for example:

The water-lilies grow beneath the stream; their broad leaves float on the surface of the water.

Re-write that in verse form and it’s a poem – isn’t it? I am particularly struck by the similar vowel sounds in “grow” and “float” (“assonance” in poetical terminology) that form a kind of half-rhyme with one another.

The water-lilies grow

Beneath the stream,

Their broad leaves float

On the surface of the water.

These lines also sound as if they could be from a poem:

The butterflies flutter from bush to bush and open their wings to the warm sun.

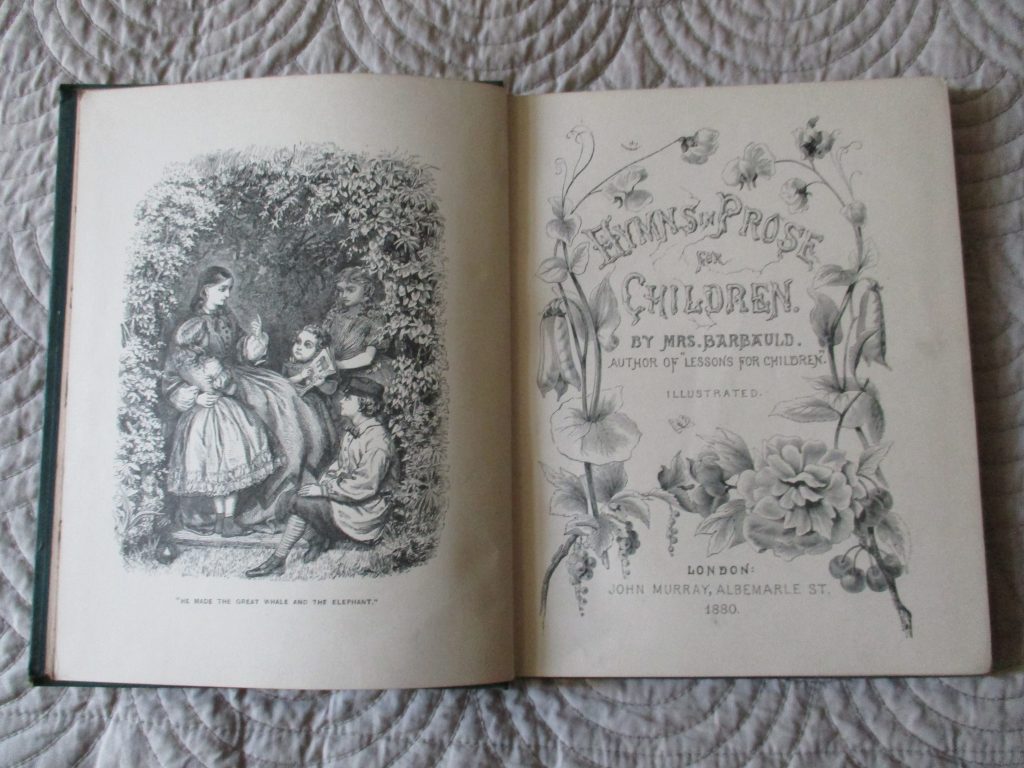

I think it’s a shame Anna Barbauld didn’t write poetry for children. If she had, I wouldn’t be surprised if there were anthologies today still including one or two. Not that her “measured prose”, her psalm-like, sermon-like religious recitations concerning the rights and wrongs of the world weren’t successful. Hymns in Prose was a very popular book, running to many editions. It was still going strong a century later, as the above image of an edition from 1880 (published by John Murray) shows. And fortunately many writers have disagreed with this stance on poetry for children, including Mrs Barbauld’s own niece, Lucy Aikin. Miss Aikin was a serious historical writer and the author of Epistles on Women (1810), but she clearly saw the value in poetry as an educational tool, selecting the contents of the anthology Poetry for Children (1801). Alongside verse by great names, this volume includes a spattering of “anonymous” poems that are simpler in nature and clearly aimed at engaging quite a young audience.

Finally, to give a slightly clearer picture of Hymns in Prose, here is part of Hymn VIII, a vision of the perfect late Georgian family, country-dwelling and god-fearing:

See where stands the cottage of the labourer covered with warm thatch! The mother is spinning at the door; the young children sport before her on the grass; the elder ones learn to labour, and are obedient; the father worketh to provide them food: either he tilleth the ground, or he gathereth in the corn, or shaketh his ripe apples from the tree. His children run to meet him when he cometh home, and his wife prepareth the wholesome meal. The father, the mother, and the children make a family; the father is the master thereof….

they kneel down together and praise God every night and every morning with one voice; they are very closely united, and are dearer to each other than any strangers.

Amongst other sources (such as the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography and the Chambers Biographical Dictionary of Women) I have used the Poetry Foundation’s page on Anna Barbauld; their full piece on the subject can be found here:

https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poets/anna-laetitia-barbauld